Humpback whales’ (Megaptera novaeangliae) habitat use in low-latitude breeding grounds is well documented from decades of coastal research. Yet, the use of pelagic habitats during the breeding season and migration has only recently been given attention.

In New Caledonia, an archipelago located in the Pacific South West, several seamounts and banks play an important role for the local humpback whale population. Yet, the reason why whales would aggregate and move between these offshore waters remains unknown. The relative abundance of maternal females in these unsheltered waters is also puzzling, in comparison to the shallow coastal waters usually occupied by these groups.

Using the newest satellite tracking technology, this project aims at understanding the environmental and social drivers of humpback whale oceanic habitat use during the breeding season. Dive depth will be related to environmental context in order to shed light on the role played by offshore seamounts for humpback whales of the Pacific South West.

This study case will provide a unique opportunity to understand the spatio-temporal scale of the humpback whale floating lek systems and explore the drivers of habitat selection during the breeding season.

This work is part of the WHERE project supported by the New Caledonian Government, the French Ministère de la transition écologique et solidaire, the World Wildlife Fund.

The « Whales of the deep » project is supported by the Louis M. Herman research scholarship (Society of Marine Mammalogy).

April 2020 update: project wrap-up

[by Solène Derville]

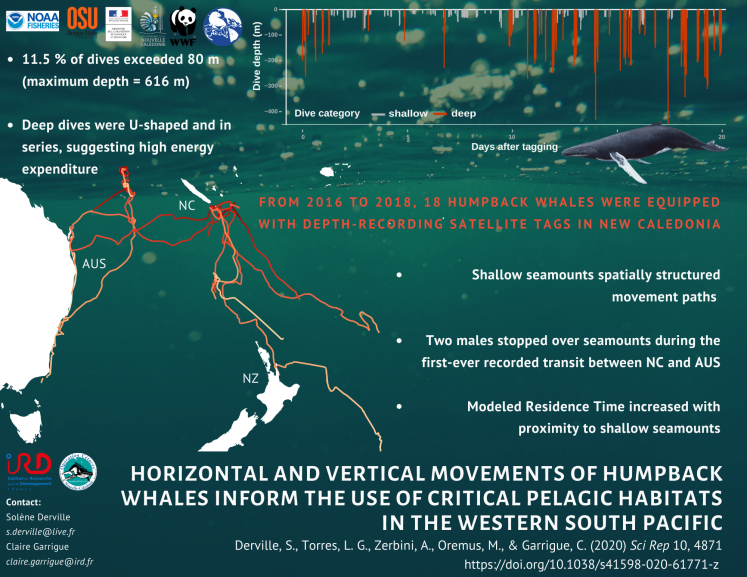

As a result of the « Whales of the deep » project, a paper was published in Scientific Reports in March. And it is accessible to everyone in open-access at this link. This study was conducted by the IRD and the NGO Opération Cétacés, with the financial and technical support of the World Wildlife Fund, the government of New Caledonia and the French Ministère de la Transition Ecologique et Durable, in collaboration with Oregon State University and NOAA (US). It could not have been possible without the Louis M. Herman research scholarship that funded the last months of my PhD. Here is short summary of our findings.

From 2016 to 2018, we conducted surveys at sea and deployed 18 satellite tags on humpback whales encountered in remote areas of the Natural Park of the Coral Sea. The results, published in Scientific Reports, confirm that seamounts are crucial habitats for reproduction and migration of this population of humpback whales, still considered as « endangered » in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. In addition, the study reveals unexpectedly deep dives and raises new questions about humpback whale behaviour in tropical offshore waters.

Humpback whale behaviour under the tropics is well documented from decades of coastal research, but their pelagic habitat use patterns remain mostly unexplored. In New Caledonia, an archipelago located in the Pacific South West, surveys at sea and satellite telemetry conducted in the last decade have revealed new habitats for humpback whales. Between 2016 and 2018, 18 satellite tags were deployed on adult humpback whales, both males and females, the latter sometimes accompagnied by a calf, in order to better understand the use of offshore tropical waters during the breeding season.

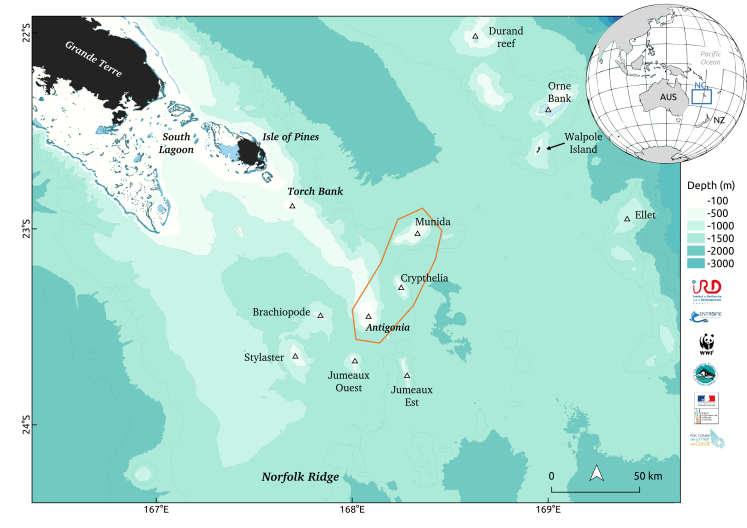

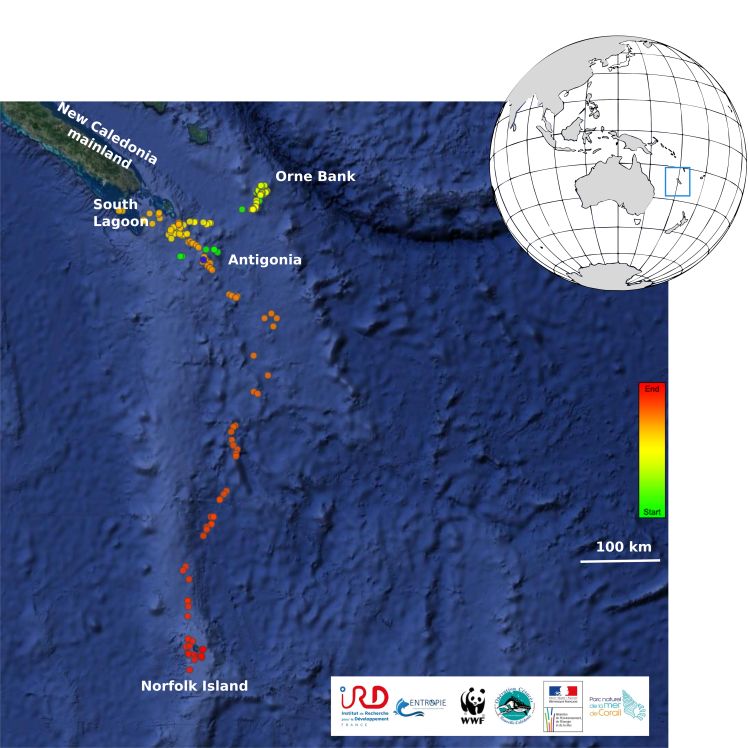

Seamounts are just like underwater mountains, rising from the bottom of the ocean without reaching its surface. Humpback whales appear to congregate around these seabed structures, specifically the shallowest, which summits are not deeper than 200 m. Humpback whales spent time over small seamounts south-west of New Caledonia, but also over the remote Lord Howe seamount chain located about 700 km from New Caledonia. In fact, two males stopped over these seamounts during the first-ever recorded migration between New Caledonia and the Australian east coast, suggesting new patterns of connectivity across the Coral Sea.

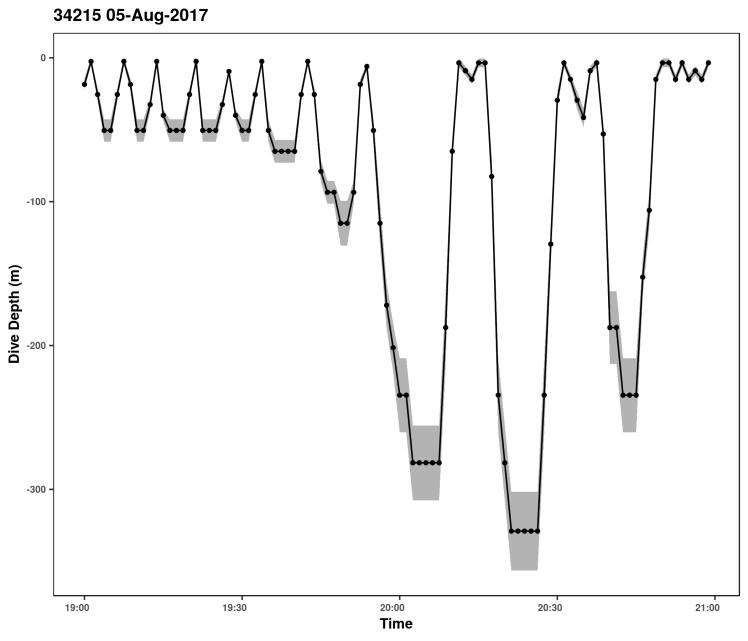

In addition to humpback whale movements, the tags also recorded the depth and duration of their dives below the surface of the ocean. Most of the 7,986 dives recorded were shallow (between the surface and 80 m deep), but deep dives were also regurlarly recorded, up to the record-breaking depth of 616 m. These dives suggest a high energy expenditure which function is not yet known. Several hypothesis are proposed to explain this unique diving behaviour : navigation, social interactions and communication, or perhaps opportunistic supplemental feeding ?

This study provides new insights into the formerly overlooked use of pelagic habitats by humpback whales during the breeding season. Given increasing anthropogenic threats on deep sea habitats worldwide, this work has implications for the conservation of vulnerable marine ecosystems.

Reference : Derville, S., Torres, L.G., Zerbini, A.N., Oremus, M., Garrigue, C. (2020) Horizontal and vertical movements of humpback whales inform the use of critical pelagic habitats in the western South Pacific. Sci Rep 10, 4871. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61771-z

August 2019 update

[by Solène Derville]

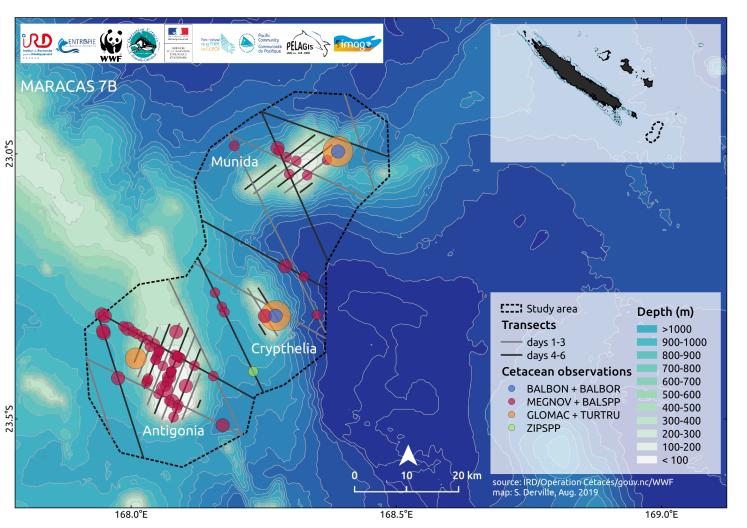

We are at the peak of the breeding season here in New Caledonia, and it’s time for a sum up. Two MARACAS-7 surveys have already been conducted this winter, one is about to finish, and the fourth will take place at the end of September. The goal of the MARACAS-7 surveys is to characterize pelagic ecosystems around seamounts, and understand the social and environmental drivers of humpback whale aggregations around these seabed structures (see previous post).

Working in remote offshore waters is not an easy task. The success of the missions entirely relies on weather. Located more than 100 km south-east of the mainland, our study site must be joined facing the trade winds and the swell. During our first cruise in June we actually never reached the seamounts! Sometime during the night transit we had to fall back as the boat could no longer stand the 3 m high swell and 30 knots of wind…

Luckily, the cruises in July and August benefited from great weather conditions, which even allowed us to detect small and elusive cetaceans such as beaked whales and dolphins. What a marvel to see these creatures swim at the bow of the ship in waters flat like a mirror (Fig 1)!

In addition to many humpback whales, we managed to identify at least five other cetacean species during these two cruises (Fig 2). As we hypothesized, most of these animals were observed near seamount summits (Fig 3). Although Antigonia concentrated most of the humpback whale observations, the other two seamounts (Crypthelia and Munida) provided observations of other baleen whales (Sei whales, Antarctic Minke whales) or odontocetes (tropical pilot whales, bottlenose dolphins). In total, 128 groups of cetaceans have been observed within 1500 m of the ship during the MARACAS cruises 7B and 7C.

Our study of the micronekton communities (i.e. pelagic organisms between 2 and 20 cm in length) has also been quite successful. Trawl samples were collected 28 times, over 12 stations scattered over the study area (Fig 4). Trawling is a fishing technique where a a net is dragged behind a boat to catch pelagic organisms in the water column. Surface trawls were conducted between 50 and 150 m, while deep trawls were conducted up to 580 m!

Micronekton is a key element in the pelagic food chain. Although humpback whales are generally known to fast during the breeding season, the “whales of the deep” project has shown some intriguing dive patterns that resemble feeding dives (Fig 5). Indeed, the SPLASH tags (Wildlife computers) deployed on 18 whales in New Caledonia have revealed deep (up to 616 m!) and repeated U-shaped dives which could suggest opportunistic feeding around ocean ridges.

Studying the micronekton community is conjunction with cetacean presence takes us a step further into understanding why humpback whales intensively use seamounts in New Caledonia. Thanks to our collaborators from the Oceanic Fisheries Program in the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) we will determine what kind of snack is available in seamount waters…

April 2019 update

[by Solène Derville]

After finishing the analysis of the satellite tracking and diving data collected on New Caledonia humpback whales between 2016 and 2018, I spent the last months turning all this data into a scientific publication. While my manuscript is in review in my co-authors’ hands, I can focus on the big task to come: the austral winter 2019.

As part of my postdoctoral work, I will be in charge of four MARACAS* 7 cruises conducted aboard the Alis oceanographic vessel from June to September. The goal? Survey a group of three shallow seamounts located south of the New Caledonia mainland. By doing so, we aim to understand why humpback whales appear to favor certain seamounts over others, and ultimately know what are the adaptive advantages to using these offshore unsheltered habitats during the breeding season.

Among these three seamounts (Fig. 1), one is a well known aggregation spot and breeding ground: the Antigonia seamount (Derville et al. 2018). Reaching 60 m below the surface, this seamount is characterized by a typical “guyot shape”, which defines a small underwater plateau with steep slopes. On the contrary, Crypthelia and Munida seamounts, the other two study areas with equally inspiring names, are not known for being used by whales during the breeding season. Indeed, almost none of the dozens of whales tracked in the region have stopped over these seamounts (Garrigue et al. 2015).

A set of multi-disciplinary research techniques (Fig. 2) will be applied in collaboration with other physicists and biologists of the Institute of Research for Development (UMR Entropie & US IMAGO) and the Secretariat of the Pacific Community, SPC, (Oceanic Fisheries Program). During the day, the study area will be surveyed using a distance sampling approach. This method provides a robust estimate of animal densities, which can then be related to habitat characteristics. Hence, environmental conditions will also be closely monitored using a combination of devices measuring parameters such as currents, temperature, salinity, or, turbidity; both at the surface and at depth. As seamounts are known for affecting ocean circulation, we are expecting to observe variable patterns of turbulences around seabed structures. We will also be recording for humpback whale songs and other cetacean sounds over the Antigonia seamount using a moored hydrophone.

Finally, given the enhanced primary productivity often encountered over seamount slope, it is also possible that seamounts offer opportunistic feeding spots for humpback whales during the breeding season or early migration. In collaboration with SPC colleagues, we will be estimating the presence and the composition of the micronekton community (i.e., pelagic fish and crustaceans between 2 and 20 cm) to look for potential preys for cetacean predators.

There is no time to waste! As my friend Dawn Barlow once said “the seamounts are calling and I must go”.

*MARACAS cruises: MARine mAmmals of the CorAl Sea

References:

Garrigue, C., Clapham, P.J., Geyer, Y., Kennedy, A.S. & Zerbini, A.N. (2015) Satellite tracking reveals novel migratory patterns and the importance of seamounts for endangered South Pacific Humpback Whales. Royal Society Open Science, 2, 150489.

Derville, S., Torres, L.G. & Garrigue, C. (2018) Social segregation of humpback whales in contrasted coastal and oceanic breeding habitats. Journal of Mammalogy, 99, 41–54.

November 2018 update

[by Solène Derville]

A couple of weeks ago, I had the pleasure (and relief) to finally submit my PhD thesis after 3 years studying the spatial ecology of humpback whales in the South Pacific. Although the hardest part of the job is now behind me, I still have one big task ahead: the PhD defense.

This exercise is completely different from that of writing a thesis. Here, I am asked to summarize my research in a 40 minutes talk rather than a 300 pages manuscript. Concision is therefore paramount. In such case, what best than a good looking map? And to represent animal movement, what best than a good looking animated GIF?

To help my jury get a better view of humpback whale movements in the Coral Sea I produced an animated GIF of the 18 tracks that we acquired between 2016 and 2018. The implanted tags that we deploy on humpback whales are equipped with an ARGOS geolocation system. This system is very different from the GPS with which most people are familiar. In practice, ARGOS systems have one big drawback: the accuracy of the positions can vary on the scale of a few kilometers to a few dozen kilometers. As a result, raw locations acquired with ARGOS tags need be processed and cleaned before use.

Using a custom made code in R, I “smoothed” my whale tracks. Between other things, this means removing locations on land, with low quality or those leading to unrealistic speeds (18 km/h in my case). Finally, I used a Correlated Random Walk (crwl R package) to interpolate my tracks at one location every 6 hours (instead of having positions acquired at uneven time intervals).

Although several packages exist to produce animations directly in R, I found it easier to simply produce a series of images in .jpg, store them in a folder, and then use a free website to produce the GIF (see gifmaker.org). And here the result!

And here is the R code to produce this map:

library(ggplot2) library(png) library(grid) library(RColorBrewer) library(plyr) # Dataframe of ARGOS whale positions (in a EPSG4326 reference system: lat long) load("crawl_argos_df.RData") # Raster of bathymetry converted to a dataframe format load("bathyNOAA_southpacific_df.RData") # version of the bathymetry limited to -2000 m to highlight shallow areas/ seamounts etc bathyNOAA_df_shallow <- bathyNOAA_df bathyNOAA_df_shallow[bathyNOAA_df_shallow$z < (-2000),]$z <- -2000 # Shapefile of reef polygons converted to a dataframe format load("reef_shallow_df.RData") # Images to be inserted as .png inside the map img <- readPNG("whale-silhouette-png.png", TRUE) bandeau <- readPNG("bandeau horizontal MARACAS 2018.png", TRUE) # create discrete colour scale for whale tracks colour_whales <- colorRampPalette(brewer.pal(11, "Spectral")[c(1:5,7:11)])(12) colour_whales <- c(colour_whales, colorRampPalette(brewer.pal(11, "PiYG")[c(1, 2, 4)])(3)) colour_whales <- c(colour_whales, colorRampPalette(brewer.pal(11, "PuOr")[c(1:3)])(3)) set.seed(2) colour_whales <- sample(colour_whales) # produce each image in a loop # locations are separated by 6 hours intervals and the longest track has 256 locations # the crawl_df contains the locations, with column "id" indicating the name of tag for (i in seq(1,256,1)){ crawl <- ddply(crawl_df, ~id, function(d) { d <- d[1:i, ] d <- d[!is.na(d$id), ] # remove NA rows for dataframe that are shorter than i d$index <- c(1:nrow(d))/nrow(d) return(d)}) crawl_last <- ddply(crawl, ~id, function(d) { d <- d[nrow(d), ]}) # select only the last position # produce map g <- ggplot(crawl, aes(x = lon360, y = lat)) + geom_tile(data = bathyNOAA_df, aes(x, y, fill = z)) + scale_fill_distiller(palette = "Blues", direction = -1, guide = F) + stat_contour(data = bathyNOAA_df_shallow, aes(x, y, z=z), binwidth = 500, color = "grey60", size = 0.2) + geom_polygon(data = reef_shallow_df, aes(long, lat, group = group), fill = "darkgrey", col = "transparent") + geom_map(data = world_map, map=world_map, aes(x = long, y = lat, map_id = id), fill = "black") + geom_path(aes(lon360, lat, group = id, col = id), size = 1.5) + scale_color_manual(values = colour_whales, guide = F) + geom_polygon(data = land_df, aes(long, lat, group = group), fill = "black", col = "black") + geom_text(aes(x = 165, y = -19.5, label = "New Caledonia"), size = 7) + geom_text(aes(x = 151.1, y = -22, label = "Australia"), size = 7) + xlab("longitude") + ylab("latitude") + theme_void() + scale_x_continuous(lim=c(150, 170)) + scale_y_continuous(lim=c(-28, -18)) + coord_fixed(expand = F) + annotation_custom( rasterGrob(bandeau), xmin = 150.5, xmax = 156, ymin = -19.8, ymax = -18.2) # add the colour whale silhouettes over the last location of each individual track for(j in 1:nrow(crawl_last)){ if (crawl_last$lon[j] < 170 & crawl_last$lon[j] > 150 & crawl_last$lat[j] < -18 & crawl_last$lat[j] > -28){ g <- g + annotation_custom( rasterGrob(img), xmin = crawl_last$lon360[j]-0.21, xmax = crawl_last$lon360[j]+0.21, ymin = crawl_last$lat[j]-0.21, ymax = crawl_last$lat[j]+0.21 ) img_col <- readPNG(paste("./whale_silhouettes_18/whale-silhouette-png-", j, ".png", sep =""), TRUE) g <- g + annotation_custom( rasterGrob(img_col), xmin = crawl_last$lon360[j]-0.18, xmax = crawl_last$lon360[j]+0.18, ymin = crawl_last$lat[j]-0.18, ymax = crawl_last$lat[j]+0.18 ) } } # save the plot as .jpg in a separate folder ggsave(plot = g, file = paste("./anim_soutenance_coralsea/image_", i, ".jpg", sep = ""), width = 400, height = 200, dpi = 300, units = "mm") }

October 2018 update

[by Solène Derville]

The whale season is almost behind us and it is time to analyze all the data we acquired this winter. As mentioned in the previous post (see below), the photo-identification of individuals is one of the routine monitoring method that we use in the field. Indeed, humpback whales can be individually identified based on the trailing edge and black-and-white patterns on the underside of their fluke. Every year, we photograph as many individuals as possible in the field and compare these pictures to the catalog of the New Caledonia humpback whale population. To date, this catalog includes more than 1500 unique individuals. Given the small size of the New Caledonia population, individuals are relatively frequently resighted across and among breeding seasons. As a result, cataloged whales have “sighting histories”, which allow us to retrace their movements and life events through time.

And just by chance, fieldwork sometimes surprises us with unexpected coincidences… The history of “Zealandia”, a whale tagged in July over the Antigonia seamount, is a case in point. Zealandia was one of the first whales observed when we arrived over the seamount on the early morning of July 17th, 2018. It was later resighted in a competitive group and tagged that same day. Although the whale did not show its fluke during the focal follow, its white flanks had been photographed on both sides and were quite distinctive… now we usually do not compare the photographs of dorsal fins and flanks because it would be too time consuming. Genetic analysis of biopsy skin samples allows the identification of individuals in such case. But we were so eager to know who this whale was that we made an exception and scrolled through the thousands of dorsal photographs we had in the catalog. And Eureka! We found the whale’s identity, which will later be confirmed through genetic analysis. Referenced under the code “HNC524”, this individual turned out to be quite exceptional…

Zealandia is a female humpback whale observed for the first time in 2001 on a small bank located south of the New Caledonia mainland. She was then resighted in 2008, 2009, 2010… with a calf on each occasion. This may not seem incredible to someone who is unfamiliar with the biology of humpback whales… but let me explain why I am making such a fuss about this particular one. Humpback whales are known for having a birth interval of about 2-3 years.

Females breed in the winter in their tropical breeding ground, migrate to their feeding ground, come back on the next year to give birth and migrate one more time accompanied by their calf. Calving in consecutive years is therefore though to be very rare… Yet, recent evidence from population dynamics modeling in New Caledonia suggests otherwise. Among the 452 females resighting histories analyzed by Chero et al. (In review), Zealandia is the only one known to have given birth three years in a row.

So how does this link back to our satellite tracking project? Well, individual movements are best interpreted if we know as much as possible about the whale’s past. As it happened, after she was tagged, Zealandia visited three major breeding grounds located in the southeastern New Caledonian waters: Antigonia, Orne bank and the South Lagoon. Why did she purposefully cover these important distances to visit several spots, both coastal and offshore? Although at the time she was tagged she was not with a calf, she could have given birth later in the season. Progesterone analyses to be conducted on the blubber sample collected in the biopsy will tell us whether she was pregnant at the time of tagging. If she was not, this roaming behavior could be interpreted as a search for mating opportunities. Given how early she started her migration south (around August 2nd), this hypothesis is quite likely.

Finally, Zealandia was tracked during part of her journey toward the Southern Ocean feeding grounds. Interestingly, she spent about a week around Norfolk Island, located a few hundred kilometers northwest of New Zealand. This observation confirms the importance of this island as a stop-over or perhaps a resting site during the humpback whale migration.

In the end, we managed to bring to light a small part of a humpback whale’s mysterious life by combining multiple research approaches. Understanding the movements and behaviors of these elusive creatures is a challenge for scientists, but it feels very rewarding to occasionally catch a glimpse of an whale’s life. So wait for the next update to hear another whale’s story!

References

Chero, G., Pradel, R., Gimenez, O., Bonneville, C., Derville, S., Garrigue, C. (In Review) High breeding capacity highlights recovery potential of humpback whale populations in the Southern hemisphere. Animal Conservation.

August 2018 update

[by Solène Derville]

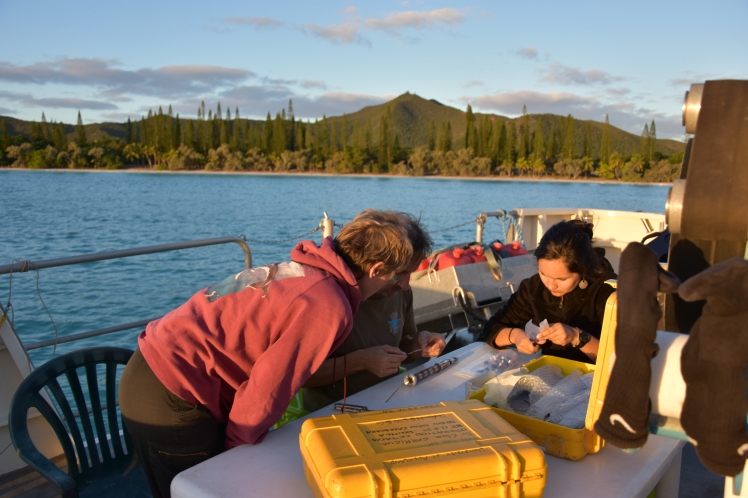

It has now been more than two months since the first humpback whales showed up in New Caledonia for their annual breeding season. In July, our team composed of members of the French Institute of Research for Development, the Opération Cétacés NGO and the World Wildlife Fund, left the Nouméa harbour aboard the Amborella. This year again, the New Caledonian government supported our project by providing this large vessel, which allows us to survey in the open ocean.

The goal for this cruise was clear: deploy 6 satellite tags on adult humpback whales at the Antigonia seamount (see previous blogpost). Tags are deployed on adult whales only, at the front of the dorsal fin, using a modified pneumatic line-thrower (called “ARTS”, see video below). While being tagged, whales are also photographed and biopsied in order to obtain the sex (through molecular sexing from the skin sample) and the identity (through genotyping and photo-identification) of the animal. These informations are essential to reconstruct the “capture history” of the tagged whales, that is where and when it has been observed in the past.

Despite rough weather on the first day (20 knot wind and big swell!) we managed to deploy two tags. The others followed on the next day at sea. Tagging 12 m long whales is one of the toughest job I have ever witnessed in the field. A great level of precision and communication among crew members is essential for this task to succeed. So you can imagine our joy when we managed to deploy 4 tags in a single day!

This short video presents the method for tag deployment from a small semi-inflatable boat using a modified pneumatic line-thrower (in 2017 for whale « Sial » and 2018 for whale « Gondwana »). The crossbow is used simultaneously to collect a biopsy sample (a small piece of skin and blubber).

One unexpected challenge that follows tagging is… finding names! For this year’s batch we went for the “geology theme”, with a special South Pacific touch… Whales were nicknamed: Pangea, Gondwana, Zealandia, Oceania, Nazca, and Tethys. Hopefully lucky names that will make these tags last for long!

Once the tags deployed we were free to use our remaining time at sea to visit other areas. We therefore decided to visit the Ellet seamount near Walpole Island (see previous blogpost), a previously unsurveyed seamount that had been used by a whale tagged in 2016. Surely enough, whales were found there! Photographies and skin samples collected there will help us understand the connexion between this new seamount and neighboring pelagic breeding grounds.